Animal Disaster Response in 2025

Animal disaster response requires urgency, but field work requires a plan.

“…most animal services agencies globally are under-staffed and ill-equipped to tackle the management and operations of a large-scale disaster…”

Animal disaster response is complicated; that’s a fact. There are persistent challenges with training, equipment, and retention of professional responders in the animal disaster response space, and yet the reality remains that whatever organization or entity may have jurisdiction (legal authority) for animal services work in the disaster area is responsible for any official response in its totality. At the same time, most animal services agencies globally are under-staffed and ill-equipped to tackle the management and operations of a large-scale disaster, let alone their normal day to day operations. Some organizations are fortunate enough to have the resources to be proactive and effective during disasters, but even these can face catastrophic events that exceed their capabilities in the short or long term. The enduring reality for most animal services organizations is that they simply do not have the fiscal, personnel, and equipment resources necessary to respond effectively to large-scale incidents. This is an understandable reality, but stands painfully at odds with increasing expectations from the community and attention from the press. It is therefore necessary for organizations to coordinate, collaborate and prepare. But what does this really mean?

There are a lot of facets to this complex problem, but I see four elements as being of the highest importance.

First, we need to emphasize standardization and interoperability across counties, states, countries and regions, as applicable. It’s worth asking a few questions to query how much you and your organization have thought this through. Have you standardized what a disaster area assessment looks like? This is critical in the first 48 hours in order to calculate resource needs, including initial mutual aid requirements. Have you standardized response roles, including across leadership and support functions? These roles are not universal to all disaster types and sizes, but many of the functions need to be performed to some scale in every event. Do you use the same vernacular to describe problems and resources (taking into account actual language differences)? Using the same language to describe roles, resources, and actions helps reduce misunderstanding and wasted resources. Are you training to the same standards and do those standards hold up to any contractual obligations, labor laws, and legal concerns? Disaster work can come with a lot of risk, so it’s important that both organizations and personnel are properly trained, equipped and protected in every sense of the word.

Second, we need to be communicating on a regular basis about disasters, from the local level outward. Identify your stakeholders, both government and private, and prioritize having conversations now, before a disaster strikes. It’s universally true that relationships need trust, and trust is not established for the first time when response is needed. A longtime American RedCross operations lead is commonly quoted for saying “We don't make friends at 2am.” Trust takes time and communication. Time spent on relationship building is always well spent. Not only will it help your organization get a seat at the table from the onset, but it will help you highlight assets and liabilities related to animal services work.

Third, we need to formalize relationships in advance. Some variation of a Mutual Aid Agreement (MAA) or Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU) should be negotiated in advance and refreshed regularly. Many organizations set intervals of three years for these agreements so that they don’t take time every year. Whatever the interval, it’s vital that roles and responsibilities be outlined in writing long before the work needs to be done. Time writing agreements during disasters is time that could be better spent on response. Start negotiating these locally and expand outward. Keep in mind there may be valuable allies at the national or international level, but remember, the further the distance and bigger the organization, the longer the response time. Agreements should clearly outline what each organization is willing to commit to and who is responsible for costs associated with a response. Most of these agreements should not commit any organization to a costly, resource consuming response, but should create the mechanism through which a response can be mounted if and when the circumstances warrant.

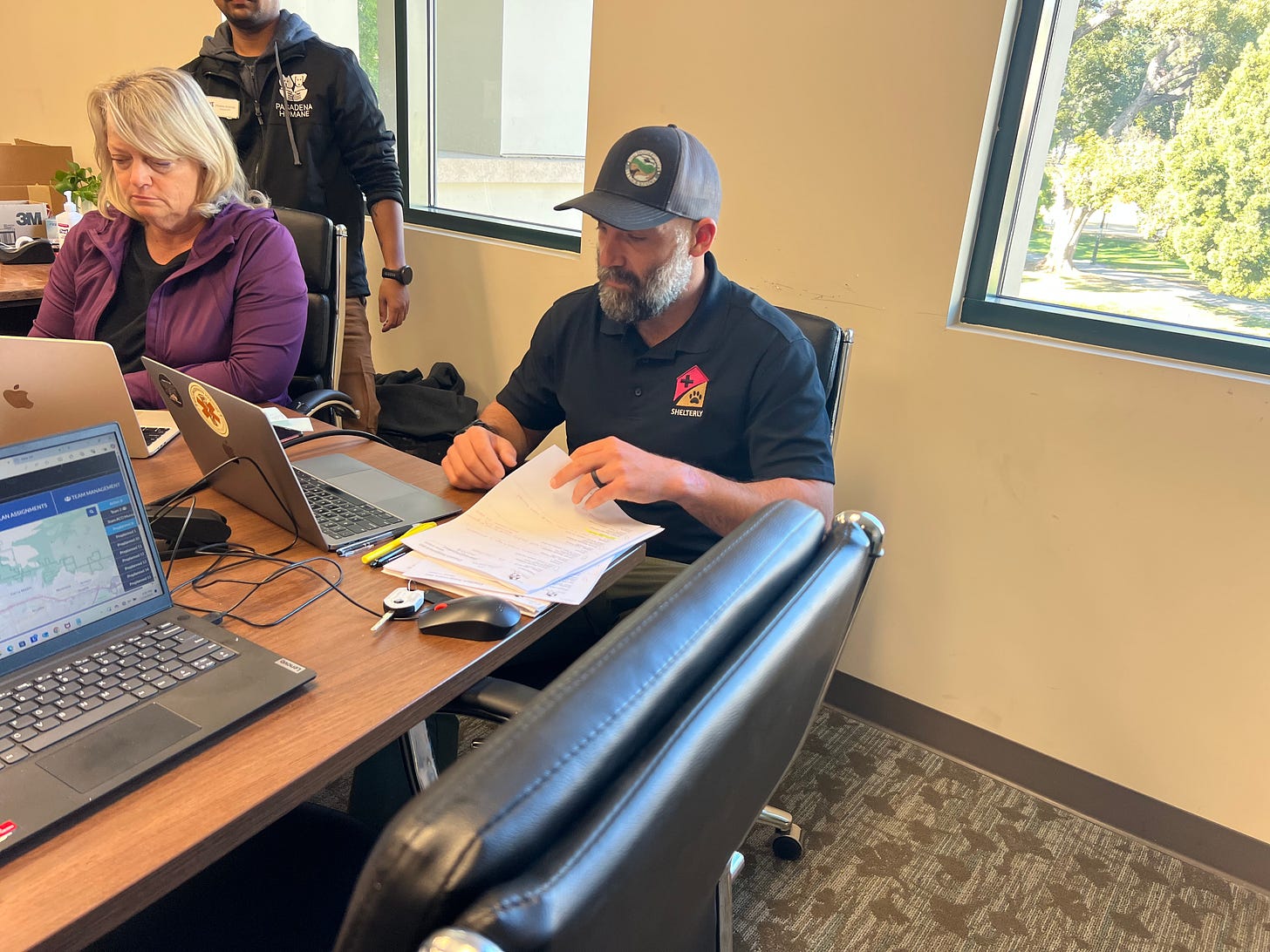

Fourth and last, we need to utilize systems and technology that can keep up with the complexity of our times. Paper systems that require on-site presence are no longer sufficient, nor are software systems that impede volunteer and mutual aid partner use. If you are using shelter and/or field services software that is restricted to your internal users and cumbersome, then it’s likely to be a major chokepoint during medium and large scale deployments. The following are systems that, while not all available in every location, are showing promise as tools that help keep disaster response for animals organized, professional, and efficient. To be clear, I am not at this time compensated by any of these platforms. I’ve seen them all work very well, most recently on the Eaton and Palisades fire in Southern California where I helped to set up response systems in the initial days for both Pasadena Humane and the City of Los Angeles. The following are only brief summaries of their use and capabilities:

CalTopo (www.caltopo.com) This is a mapping software application designed for human search and rescue operations. In parts of the US, the system is updated automatically with fire specific map layers including satellite heat maps and incident boundaries. Service calls can be uploaded to the platform and downloaded in multiple formats and this data can be displayed on any device. Maps work offline when set up correctly and can be used to track response elements in real time either through cellular connections or satellite tracking devices. This tracking data gives leadership rich information for search planning and reporting, as it shows exactly where teams have been in the field and with what frequency. Field teams can drop pins with notes and photos if they generate their own calls, observe work that needs to be done, and/or need to pass on information about Service Requests (SRs, or individual cases that need to be worked) for their future selves or other teams. This helps to convey information such as property access, trap locations, feeding information and more. Seeing Service Requests, tactical intelligence, tracking, and incident information in a customizable geospatial format can be invaluable for leaders, responders, and government agencies at higher levels of a response. CalTopo has a functional free version, and paid versions start at $250 USD per year for nonprofits, $500 per year for for-profit entities, which includes 10 admin accounts and unlimited users (admins make and maintain maps, but users can access them and add data if given write permission). Access can be restricted in a variety of ways including both temporary access and level of access. I have also used this platform for field work in Saudi Arabia, and it worked very well. It will work in most places.

Shelterly (www.shelterly.org) is a non-profit organization that has developed software and systems for organizing animal disaster response. The software prioritizes simple training, intuitive processes and data confidentiality in its five main modules including Hotline (information into the software), Dispatch (sending teams to do work), Shelter (modular, temporary shelters), Veterinary (triage, veterinary requests, and medical records), and Reporting. Organizations can easily add users with access tokens, create new events, and manage their own data. During most disasters, animals remain at the property of their owners for an extended period of time, and Shelterly allows organizations to maintain owner, animal, shelter, and medical records without the choke point of traditional shelter software. Beyond the robust software, Shelterly has developed systems that streamline all of the information requirements of animal disaster response and has innovated in ground-breaking ways including automated hotline numbers, off-site data entry/processing, remote dispatch, mission pre-planning, on-site intelligence and search management functions, remote debriefing of field teams, and more. The software uses the Google API for mapping data and is currently configured for use in the US and Canada. Finally, while Shelterly is a cutting-edge software tool, field responders are handed a printed packet every morning with a list of the calls they have been assigned. This allows them to work effectively without an internet connection and the paperwork requires them to fill in basic, essential information after each call so that the system can be updated later with resolutions or ongoing needs. Shelterly works for all species of animal and has strong integration with CalTopo.

Petco Love Lost (www.petcolove.org/lost) is a free pet reunification platform that uses the power of photo-matching technology; upload a photo of a lost or found pet and Petco Love Lost instantaneously searches community reports of lost and found pets, plus thousands of animal shelters and pets posted to Nextdoor and Neighbors by Ring. It’s the primary lost-and-found reporting tool routinely used by most animal shelters in the US and is a crucial tool for reunification during disasters as well. As of publication, Petco Love Lost is in the process of connecting with Shelterly so that animals found by response agencies will automatically be flagged to those who have lost an animal, thereby speeding up the process of reunification. Love Lost is a free service and currently works in the US and Canada for cats and dogs.

Google Drive (various applications) allows managers to easily share information with staff and volunteers across agencies. Data that is sensitive for any reason should be kept in normal business systems, but the core information that responders need, such as lodging, meal, supply, schedules, and much more, can be easily shared through a variety of Google documents. I typically produce an Incident Action Plan and an Operations Manual for each incident by the end of the first day, and make those documents available to all responders so that they all have access to the information they need and so that we, as leaders, can meet our obligation of setting out clear expectations and therefore hold people accountable. Make sure to change the share setting as appropriate.

Whatsapp (www.whatsapp.com) may seem like an outlier on this list, but it is a free and powerful tool that has been shown to improve disaster coordination globally, especially when used efficiently. Animal Services agencies tend to use a variety of communications systems internally, but this is another major limiting factor during disaster response when outside agencies, volunteers, and others are asked to step in and help. While direct communication via reliable radio systems remains ideal for communication, coordination, and responder safety, Whatsapp can fill the gap when these systems are not available or reliable. I publish a Whatsapp policy for my disaster clients, but here are a couple of tips for use:

Assign team names before sending anyone in the field and communicate with teams rather than individuals. e.g. Team 2, what is your status…Team 3 is in route to Service Request 125…Team 10 has completed Service Request 414 and is ready for a new assignment.

Put links to your Incident Action Plan and Operation Manual in the group description (Google Docs links) so that everyone has access upon entry to the group.

Create as many groups as necessary to allow people to communicate with each other at whatever level makes sense (Division, Team, Leadership, etc), but there should be one primary channel for dispatching teams, and chatting should be kept to a minimum.

Create a separate group for photos and videos. These assets should be shared to that chat by anyone in the field as part of a policy defined in an Operations Manual, and the group should include the head of external communications (in the US a Public Information Officer or PIO), and others with a communications or leadership role. This way communications staff automatically get the content they need for their purposes and they can ask anyone sharing for more information and context. This streamlines the process, as it gets people what they need without requiring them to ask for it. To be clear, a good policy is for ALL external posts to be approved by the appropriate staff.

My first animal disaster response was to Typhoon Ketsana in Manila in 2009. I’ve since taken part in many responses around the world and have too often seen leaders collapse under the strain as they are caught between unrealistic expectations and inefficient systems. My hope in highlighting some of these priorities and systems is that you, leaders in Animal Services, can get ahead through planning, the use of technology and by coordinating with each other. If you haven’t already, please join these conversations via the Animal Services Professionals Substack and the Global Animal Services Professionals LinkedIn group.

John Peaveler is the owner of Humane Innovations, a company dedicated to providing equipment, training, and consulting to animal services organizations around the world.